HTML and CSS – An absolute beginners guide

So, you’re ready to take the plunge and begin to learn how to build your own web pages and sites? Fantastic! We’ve got quite a ride ahead, so I hope you’re feeling adventurous.

Before you dive in and start to build your web site, we need to take a little time to get your computer set up and ready for the work that lies ahead. That’s what this section is all about: ensuring that you have all the tools you need installed and ready to go.

This information is an excerpt from my newly-released SitePoint book, Build Your Own Web Site The Right Way Using HTML & CSS. In the following pages, I’ll show you how to set up your computer — be it PC or Mac — so that you’re ready to build a site.

Then, we’ll meet XHTML [3] and walk through the details of how to structure a web page correctly. In the process, we’ll play around with elements, comments, and symbols, and we’ll talk about the concept of nesting. It might sound complex, but it’s not! In fact, by the end of that discussion, you’ll have a working web page that displays text, links, an image and even a quote!

Finally, we’ll turn to the topic of Cascading Style Sheets, which we’ll use to change the way elements of your web page look. We’ll discuss the different ways in which you can use styles to control the way your page looks before creating our own .css file and using it – as well as tools like selectors and spans – to spruce up our web page’s headings, text, and so on.

Don’t worry if some of these terms are unfamiliar – this excerpt, like the book itself, assumes that you have no knowledge about building web pages. The information I’ll present here basically comprises the first three chapters of the book — later chapters go on to show you how to build forms, optimize graphics for the Web, publish your site, and soup it up with plug-in tools such as blogs, image galleries, and more — the Table of Contents [4] has all the details.

But now, let’s start to set up your computer so that you’re ready to build your first web page.

Tooling Up

If you were to look at the hundreds of computing books for sale in your local bookstore, you could be forgiven for thinking that you’d need to invest in a lot of different programs to build a web site. However, the reality is that most of the tools you need are probably sitting there on your computer, tucked away somewhere you wouldn’t think to look for them. And if ever you don’t have the tool for the job, there’s almost certain to be one or more free programs available that can handle the task.

We’ve made the assumption that you’re already on the Internet — your web site wouldn’t be of much use without it! And, though it’s not essential, it will also be handy if you have a broadband internet connection. Don’t worry if you don’t have broadband: it won’t affect any of the tasks we’ll undertake in this book. It will, however, mean that some of the suggested downloads may take a while to load onto your computer, but you probably knew that already.

Planning, Schmanning

At this point, it might be tempting to look at your motives for building a web site. Do you have a project plan? What objectives do you have for the site?

While you probably have some objectives, and some idea of how long you want to spend creating your site, we’re going to gloss over the nitty-gritty of project planning to some extent. This is not to say that project planning isn’t an important aspect to consider, but we’re going to assume that because you’ve picked up a book entitled Build Your Own Web Site The Right Way, you probably want to just get right into the building part.

As this is your first web site, and will be a fairly simple one, we can overlook some of the more detailed aspects of site planning. Later, once you’ve learned — and moved beyond — the basics of building a site, you might feel ready to tackle a larger, more technically challenging site. When that time comes, proper planning will be a far more important aspect of the job. But now, let’s gear up to build our first, simple site.

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C [20]//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Untitled Document</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> </body> </html>

The markup above is the most basic web page you’ll see here. It contains practically no content of any value (at least, as far as someone who looks at it in a browser is concerned), but it’s crucial that you understand what this markup means. Let’s delve a little deeper.

The Doctype

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd">

This is known as the doctype (short for Document Type Declaration). It must absolutely be the first item on a web page, appearing even before any spacing or carriage returns.

Have you ever taken a document you wrote in Microsoft Word 2003 on one computer, and tried to open it on another computer that ran Word 97? Frustratingly, without some pre-emptive massaging when the file is saved in the first place, this just doesn’t work. It fails because Word 2003 includes features that Bill Gates and his team hadn’t even dreamed of in 1997, and Microsoft needed to create a new version of its file format to cater to these new features. Just as Microsoft has many different versions of Word, so too are there different versions of HTML, the latest of which is XHTML. Mercifully, the different versions of HTML have been designed so that this language doesn’t suffer the same incompatibility gremlins as Word, but it’s still important to identify the version of HTML that you’re using. This is where the doctype comes in. The doctype’s job is to specify which version of HTML the browser should expect to see. The browser uses this information to decide how it should render items on the screen.

The doctype above states that we’re using XHTML 1.0 Strict, and includes a URL to which the browser can refer: this URL points to the W3C’s specification for XHTML 1.0 Strict. Got all that? Okay: jargon break! There are too many abbreviations for this paragraph!

Note: Jargon Busting 101

URL: URL stands for Uniform Resource Locator. It’s what some (admittedly more geeky) people refer to when they talk about a web site’s address. URL is definitely a useful term to learn, though, because it’s becoming more and more common.

W3C: W3C is an abbreviation of the name World Wide Web Consortium, a group of smart people spread across the globe who, collectively, come up with proposals for the ways in which computing and markup languages that are used on the Web should be written. The W3C defines the rules, suggests usage, then publishes the agreed documentation for reference by interested parties, be they web site creators like your good self (once you’re done with this book, that is), or software developers who are building the programs that need to understand these languages (such as browsers or authoring software).

The W3C documents are the starting point, and indeed everything in this book is based on the original documents. But, trust me: you don’t want to look at any W3C documents for a long time yet. They’re just plain scary for us mere mortals without Computer Science degrees. Just stick with this book for time being — I’ll guide you through!

The html Element: So, the doctype has told the browser to expect a certain version of HTML. What comes next? Some HTML!

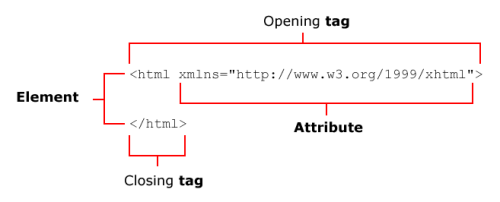

An XHTML document is built using elements. Remember, elements are the bricks that create the structures that hold a web page together. But what exactly is an element? What does an element look like, and what is its purpose?

- An XHTML element starts and ends with tags — the opening tag and the closing tag. (Like any good rule, there are exceptions to this: empty elements, such as

meta, use special empty tags. We’ll take a look at empty tags soon.) - A tag consists of an opening angled bracket (

<), some text, and a closing bracket (>). - Inside a tag, there is a tag name; there may also be one or more attributes.

Let’s take a look at the first element in the page: the html element. Figure 2.2 shows what we have.

Figure 2.2. Constituents of a typical XHTML element

Figure 2.2 depicts the opening tag, which marks the start of the element:

<html >

Below it, we see the closing tag, which marks its end (and occurs right at the end of the document):

</html>

Here’s that line again, with the tag name in bold:

<html >

And there is one attribute in the opening tag:

<html >

Note: What’s an Attribute?

HTML elements can have a range of different attributes; the available attributes vary depending on which element you’re dealing with. Each attribute is made up of a name and a value, and these are always written as name=”value”. Some attributes are optional, while others are compulsory, but together they give the browser important information that the element wouldn’t offer otherwise. For example, the image element (which we’ll learn about soon) has a compulsory ‘image source’ attribute, the value of which gives the filename of the image. Attributes appear in the opening tag of any given element. We’ll see more attributes crop up as we work our way through this project, and, at least initially, I’ll be making sure to point them out, so that you’re familiar with them.

Back to the purpose of the html element. This is the outermost “container” of our web page; everything else is kept within that outer container — there are no exceptions! Let’s peel off that outer layer and take a peek at the contents inside.

There are two major sections inside the html element: the head and the body. It’s not going to be difficult to remember the order in which those items should appear, unless you happen to enjoy doing headstands.

The head Element

The head element contains information about the page, but no information that will be displayed on the page itself. For example, it contains the title element, which tells the browser what to display in its title bar:

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Untitled Document</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> </body> </html>

The title Element

The opening <title> and closing </title> tags are wrapped around the words “Untitled Document” in the markup above. Note that the <title> signifies the start, while the closing </title> signifies the end of the title. That’s how closing tags work: they have forward slashes just after the angle bracket.

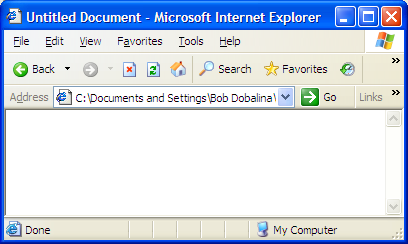

The “Untitled Document” title is typical of what HTML authoring software provides as a starting point when you choose to create a new web page; it’s up to you to change those words. However, if you’re creating a web page from scratch in a text editor (like Notepad), you will, I hope, remember to type something a little more useful. But just what is this title? Time for a screenshot: check out Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3. “Untitled Document” — not a very helpful title

It really would pay dividends to put something useful in there, and not just for the sake of those people who visit our web page. The content of the title element is also used for a number of other purposes:

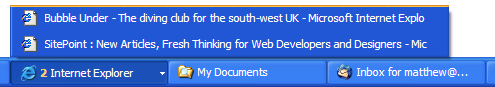

- It’s the name that appears in the Windows Taskbar for any open document, as shown in Figure 2.4. It also appears in the dock on a Mac, as Figure 2.5 illustrates. When you have a few windows open, you’ll appreciate those people who have made an effort to enter a descriptive title!

Figure 2.4. The title appearing in the Windows Taskbar

Figure 2.5. The title displaying in the Mac dock

- If users decide to add the page to their bookmarks (or favorites), the title will be used to name the bookmark, as Figure 2.6 illustrates.

Figure 2.6. An untitled document saved to IE’s favorites

- Your title element is used heavily by search engines to ascertain what your page contains, and what information about it should be displayed in the search results. Just for fun, and to see how many people forget to type in a useful title, try searching for the phrase ‘Untitled Document’ in the search engine of your choice.

#meta Elements

Inside the head element in our simple example, we can see a meta element, which is shown in bold below:

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Untitled Document</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> </body> </html>

meta elements can be used in a web page for many different reasons. Some are used to provide additional information that’s not displayed on-screen to the browser or to search engines; for instance, the name of the page’s author, or a copyright notice, might be included in meta elements. In the example above, the meta tag tells the browser which character set to use (specifically, UTF-8, which includes the characters needed for web pages in just about any language).

There are many different uses for meta elements, but most of them will make no discernible difference to the way your page looks, and as such, won’t be of much interest to you.

Note: Self-closing Elements

The meta element is an example of a self-closing element (or an empty element). Unlike title, the meta element needn’t contain anything, so we could write it as follows:

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8"></meta>

XHTML contains a number of empty elements, and the boffins who put together XHTML decided that writing all those closing tags would get annoying pretty quickly, so they decided to use self-closing tags: tags that end with />. So our meta example becomes:

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

Note: The Memory Game: Remembering Difficult Markup

If you’re thinking that the doctype and meta elements are difficult to remember, and you’re wondering how on earth people commit them to memory, don’t worry: most people don’t! Even the most hardened and world-weary coders would have difficulty remembering these elements exactly, so most do the same thing — they copy from a source they know to be correct (most likely from their last project or piece of work). You’ll probably do the same as you work with project files for this book.

Fully-fledged web development programs, such as Dreamweaver, will normally take care of these difficult parts of coding.

Other head Elements

Other items, such as CSS markup and JavaScript [21] code, can appear in the headelement, but we’ll discuss these as we need them.

The body Element

Finally, we get to the place where it all happens! The body element of the page contains almost everything that you see on the screen, including headings, paragraphs, images, any navigation that’s required, and footers that sit at the bottom of the web page.

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Untitled Document</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> </body> </html>

The Most Basic Web Page in the World

Actually, that heading’s a bit of a misnomer: we’ve already showed you the most basic page (the one without any content). However, to start to appreciate how everything fits together, you really need to see a simple page with some actual content on it. Let’s have a go at it, shall we?

Open your text editor and type the following into a new, empty document (or grab the file from the code archive if you don’t feel like typing it out — I understand completely!).

Example 2.1. basic.html <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>The Most Basic Web Page in the World</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> <h1>The Most Basic Web Page in the World</h1> <p>This is a very simple web page to get you started.

Hopefully you will get to see how the markup that drives the page relates to the end result that you can see on screen.</p> <p>This is another paragraph, by the way. Just to show how it works.</p> </body> </html>

Once you’ve typed it out, save it as basic.html.

If you’re using Notepad, select File > Save As from the menu and find the Web folder you created inside My Documents. Enter the filename as index.html, select UTF-8 from the Encoding drop-down list, and click Save.

If you’re using TextEdit on a Mac, first make sure that you’re in plain text mode, then select File > Save As from the menu. Find the Sites folder, enter index.html, select Unicode (UTF-8) from the Plain Text Encoding drop-down list, and click Save. TextEdit will warn you that you’re saving a plain text file with an extension other than .txt, and offer to append .txt to the end of your filename. We want to save this file with an .html extension, so click the Don’t Append button, and your file will be saved.

Note: The Importance of UTF-8

If you neglect to select UTF-8 when saving your files, it’s likely that you won’t notice much of a difference. However, when someone else comes along to view your web site (say, a Korean friend of yours), they’ll probably end up with a screen of garbage. Why? Because their computer is set up to read Korean text, and yours is set up to create English text. UTF-8 can handle just about any language there is (including some quite obscure ones!) and most computers can read it, so UTF-8 is always a safe bet.

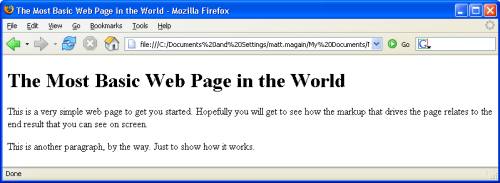

Next, using Windows Explorer or Finder, locate the file that you just saved, and double-click to open it in your browser. Figure 2.7, ‘Displaying a basic page’ shows how the page displays.

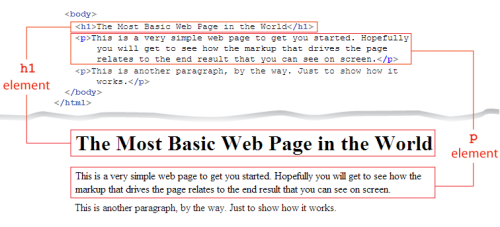

Figure 2.7. Displaying a basic page

Figure 2.7. Displaying a basic page

Analysing the Web Page

We’ve introduced two new elements to our simple page: a heading element, and a couple of paragraph elements, denoted by the <h1> tag and <p> tags, respectively.

Figure 2.8. Comparing the source markup with the view presented in the browser

Do you see how the markup you’ve typed out relates to what you can see in the browser? Figure 2.8 shows a direct comparison of the document displays.

The opening <h1> and closing </h1> tags are wrapped around the words “The Most Basic Web Page in the World,” making that the main heading for the page. In the same way, the p elements contain the text in the two paragraphs.

There’s another point to note: the tags are all lowercase. All of our attribute names will be in lowercase, too. Many older HTML documents include tags and attributes in uppercase, but this isn’t allowed in XHTML.

Headings and Document Hierarchy

In the example above, we use an h1 element to show a major heading. If we wanted to include a subheading beneath this heading, we would use the h2 element. There are no prizes for guessing that a subheading under an h2 would use an h3 element, and so on, until we get to h6. The lower the heading level, the lesser its importance and, as a rule, the smaller (or less prominent) the font.

With headings, an important (and commonsense) practice is to ensure that they do not jump out of sequence. In other words, you should start from level one, and work your way down through the levels in numerical order. You can jump back up from a lower-level heading to a higher one, provided that the content under the higher-level heading to which you’ve jumped does not refer to concepts that are addressed under the lower-level heading. It may be useful to visualize your headings as a list:

- First Major Heading

- First Subheading

- Second Subheading

- Another Major Heading

- Another Subheading

Here’s the XHTML view of the example shown above:

<h1>First Major Heading</h1> <h2>First Subheading</h2> <h2>Second Subheading</h2> <h3>A Sub-subheading</h3> <h1>Another Major Heading</h1> <h2>Another Subheading</h2>

Paragraphs

Of course, no one wants to read a document that contains only headings — you need to put some text in there. The element we use to deal with blocks of text is the p element. It’s not difficult to remember: p is for paragraph! That’s just as well, because you’ll almost certainly find yourself using this element more than any other. And that’s the beauty of XHTML: most elements that you use frequently are either very obvious, or easy to remember once you’re introduced to them.

For People who Love Lists

Let’s imagine that you want a list on your web page. To include an ordered list of items, we use the ol element. An unordered list — called ‘bullet points’ by the average person — makes use of the ul element. In both types of list, individual points or list items are specified using the li element. So we use ol for an ordered list, ul for an unordered list, and li for a list item. Easy!

To see this markup in action, type the following into a new text document, save it as lists.html, and view it in the browser by double-clicking on the saved file’s icon.

Example 2.2. lists.html <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Lists - an introduction</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> <h1>Lists - an introduction </h1> <p>Here's a paragraph. A lovely, concise little paragraph.</p> <p>Here comes another one, followed by a subheading.</p> <h2>A subheading here</h2> <p>And now for a list or two:</p> <ul> <li>This is a bulleted list</li> <li>No order applied</li> <li>Just a bunch of points we want to make</li> </ul> <p>And here's an ordered list:</p> <ol> <li>This is the first item</li> <li>Followed by this one</li> <li>And one more for luck</li> </ol> </body> </html>

How does it look to you? Did you type it all out? Remember, if it seems like a lot of hassle to type out the examples, you can find all the markup in the code archive, as I explained in the preface. However, bear in mind that simply copying and pasting markup, then saving and running it, doesn’t really give you a feel for what’s happening — it really will pay to learn by doing. Even if you make mistakes, it’s still a better way to learn (you’ll be happy when you can spot your own errors and fix them for yourself). When displayed in a browser, the above markup should look like the page shown in Figure 2.9.

There are many, many different elements that you can use on your web page, and we’ll meet more of them as our web site development progresses. As well as the more obvious elements that you’ll come across, there are others that are not immediately obvious: what would you use div, span, or a elements for? Any guesses? Don’t worry, all will be revealed in good time.

Figure 2.9. Using unordered and ordered lists to organize information

Commenting your Web Pages

Back in the garage, you’re doing a little work on your project car and, as you prepare to replace the existing tires with a new set of low-profile whitewalls, you notice that your hubcaps aren’t bolted on: you’d stuck them to the car with super glue. There must have been a good reason for doing that, but you can’t remember what it was. The trouble is, if you had a reason to attach the hubcaps that way before, surely you should do it the same way again. Wouldn’t it be great if you’d left yourself a note when you first did it, explaining why you used super glue instead of bolts? Then again, your car wouldn’t look very nice with notes stuck all over it. What a quandary!

When you’re creating a web site, you may find yourself in a similar situation. You might build a site, then not touch it again for six months. Then, when you revisit the work, you might find yourself going through the all-too-familiar head-scratching routine. Fortunately, there is a solution!

XHTML — like most programming and markup languages’allows you to use comments. Comments are perfect for making notes about something you’ve done and, though they’re included within your code, comments do not affect the on-screen display. Here’s an example of a comment:

Example 2.3. comments.html <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Comment example</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> <p>I really, <em>really</em> like this XHTML stuff.</p> <!-- Added emphasis using the em element. Handy one, that! --> </body> </html>

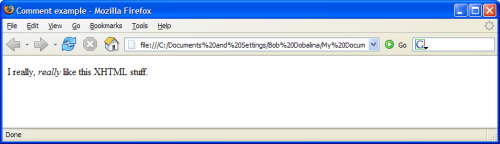

Figure 2.10 shows the page viewed on-screen.

Figure 2.10. The comment remains hidden in the on-screen display

Figure 2.10. The comment remains hidden in the on-screen display

Comments must start with <!--, after which you’re free to type whatever you like as a “note to self.” Well, you’re free to type almost anything: you cannot type double dashes. Why not? Because that’s a signal that the comment is about to end — the --> part.

Oh, and did you spot how we snuck another new element in there? The emphasis element, denoted with the <em> and </em> tags, is used wherever … well, do I really need to tell you? Actually, that last question was kind of rhetorical. It was there to make a point: did you notice that the word “really” appeared in italics? Read that part to yourself now, and listen to the way it “sounds” in your head. Now you know when to use the em element!

Using Comments to Hide Markup from Browsers Temporarily

There is no limit to the amount of information you can put into a comment, and this is why comments are often used to hide a section of a web page temporarily. Commenting may be preferable to deleting content, particularly if you want to put that information back into the web page at a later date (if it’s in a comment, you won’t have to re-type it). This is often called ‘commenting out’ markup. Here’s an example:

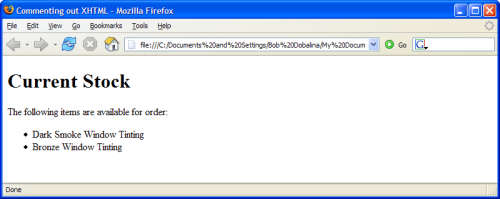

Example 2.4. commentout.html <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Commenting out XHTML</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> <h1>Current Stock</h1> <p>The following items are available for order:</p> <ul> <li>Dark Smoke Window Tinting</li> <li>Bronze Window Tinting</li> <!-- <li>Spray mount</li> <li>Craft knife (pack of 5)</li> --> </ul> </body> </html>

Figure 2.11 shows how the page displays in Firefox.

Figure 2.11. The final, commented list items are not displayed

Figure 2.11. The final, commented list items are not displayed

Remember, you write a comment like this: <!--Your comment here followed by the comment closer, two dashes and a right-angled bracket-->.

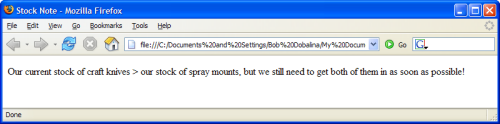

Symbols

Occasionally, you may need to include the greater-than (>) or less-than (<) symbols in the text of your web pages. The problem is that these symbols are also used to denote tags in XHTML. So, what can we do? Thankfully, we can use special little codes called entities in our text instead of these symbols. The entity for the greater-than symbol is >; we can substitute it for the greater-than symbol in our text, as shown in the following simple example. The result of this markup is shown in Figure 2.12.

Example 2.5. entity.html <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Stock Note</title><meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> <p>Our current stock of craft knives > our stock of spray mounts, but we still need to get both of them in as soon as possible!</p> </body>

</html>

Figure 2.12. The

Figure 2.12. The > entity is displayed as > in the browser

Many different entities are available for a wide range of symbols, most of which don’t appear on your keyboard. They all start with an ampersand (&) and end with a semicolon. Some of the most common are shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1. Some common entities

| Entity | Symbol |

> |

> |

< |

< |

& |

& |

£ |

£ |

© |

© |

™ |

™ |

Diving into our Web Site

So far, we’ve looked at some very basic web pages as a way to ease you into the process of writing your own XHTML markup. Perhaps you’ve typed them up and tried them out, or maybe you’ve pulled the pages from the code archive and run them in your browser. Perhaps you’ve even tried experimenting for yourself — it’s good to have a play around. None of the examples shown so far are keepers, though. You won’t need to use any of these pages, but you will be using the ideas that we’ve introduced in them as you start to develop the fictitious project we’ll complete in the course of this book: a web site for a local diving club.

The diving club comprises a group of local enthusiasts, and the web site will provide a way for club members to:

- share photos from previous dive trips

- stay informed about upcoming dive trips

- provide information about ad-hoc meet-ups

- read other members’ dive reports and write-ups

- announce club news

The site also has the following goals:

- to help attract new members

- to provide links to other diving-related web sites

- to provide a convenient way to search for general diving-related information

The site’s audience may not be enormous, but the regular visitors and club members are very keen to be involved. It’s a fun site that people will want to come back to again and again, and it’s a good project to work on. But it doesn’t exist yet! You’re going to start building it right now. Let’s start with our first page: the site’s home page.

The Homepage: the Starting Point for all Web Sites

At the very beginning of this chapter, we looked at a basic web page with nothing in it (the car chassis, with no bodywork or interior, remember?). You saved the file as basic.html. Open that file in your text editor now, and strip out the following:

- the text contained within the opening

<title>and closing</title>tags - all the content between the opening

<body>and closing</body>tags

Save the file as index.html.

Here’s the markup you should have in front of you now:

Example 2.6. index.html <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title></title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> </body> </html>

Let’s start building this web site, shall we?

Setting a Title

Remembering what we’ve learned so far, let’s make a few changes to this document. Have a go at the following:

- Change the title of the page to read ‘Bubble Under — The diving club for the south-west UK.’

- Add a heading to the page — a level one heading (hint, hint) — that reads ‘BubbleUnder.com.’

- Immediately after the heading, add a paragraph that reads, ‘Diving club for the south-west UK — let’s make a splash!’ (This is your basic, marketing-type tag line, folks!)

Once you make these changes, your markup should look something like this (the changes are shown in bold):

Example 2.7. index.html <!DOCTYPE html "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Bubble Under - The diving club for the south-west UK</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> <h1>BubbleUnder.com</h1> <p>Diving club for the south-west UK - let's make a splash!</p>

</body> </html>

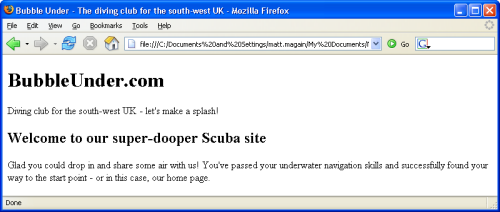

Save the page, then double-click on the file to open it in your chosen browser. Figure 2.13 shows what it should look like.

Figure 2.13. Displaying our work on the homepage

Welcoming New Visitors

Now, let’s expand upon our tag line a little. We’ll add a welcoming subheading “a second level heading” to the page, along with an introductory paragraph:

Example 2.8. index.html (excerpt) <body> <h1>BubbleUnder.com</h1> <p>Diving club for the south-west UK - let's make a splash!</p> <h2>Welcome to our super-dooper Scuba site</h2> <p>Glad you could drop in and share some air with us! You've passed your underwater navigation skills and successfully found your way to the start point - or in this case, our home page.</p> </body>

Apologies to anyone who doesn’t get my hilarious puns on diving terminology. Come to think of it, apologies to those who do — they’re truly cringe-worthy!

Hey! Where’d it All Go?

You’ll notice that we didn’t repeat the markup for the entire page in the above example. Why? Because paper costs money, trees are beautiful, and you didn’t buy this book for weight-training purposes. In short, we won’t repeat all the markup all the time; instead, we’ll focus on the parts that have changed, or have been added to. And remember: if you think you’ve missed something, don’t worry. You can find all of the examples in the book’s code archive.

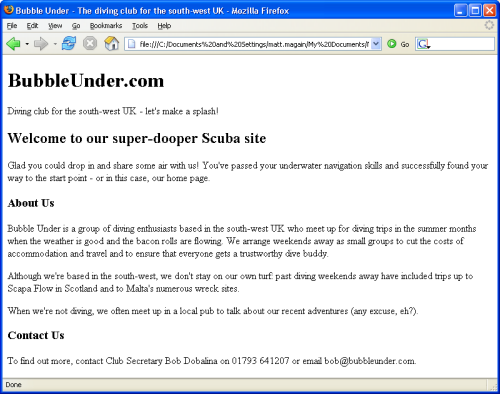

Once you’ve added the subheading and the paragraph that follows it, save your page once more, then take another look at it in your browser (either hit the refresh/reload button in your browser, or double-click on the file icon in the location at which you saved it). You should be looking at something like the display shown in Figure 2.14.

Figure 2.14. The homepage taking shape

Figure 2.14. The homepage taking shape

So, the homepage reads a lot like many other homepages at this stage: it has some basic introductory text to welcome visitors, but not much more. But what exactly is the site about? Or, to be more precise, what will it be about once it’s built?

What’s it All About?

Notice that, despite our inclusion of a couple of headings and a couple of paragraphs, there is little to suggest what this site is about. All visitors know so far is that the site’s about diving. Let’s add some more explanatory text to the page, along with some contact information:

- Beneath the content you already have on the page, add another heading: this time, make it a level three heading that reads, ‘About Us’ (remember to include both the opening and closing tags for the heading element).

- Next, add the following text. Note that there is more than one paragraph.

Bubble Under is a group of diving enthusiasts based in the south-west UK who meet up for diving trips in the summer months when the weather is good and the bacon rolls are flowing. We arrange weekends away as small groups to cut the costs of accommodation and travel, and to ensure that everyone gets a trustworthy dive buddy.

Although we’re based in the south-west, we don’t stay on our own turf: past diving weekends have included trips up to Scapa Flow in Scotland and to Malta’s numerous wreck sites.

When we’re not diving, we often meet up in a local pub to talk about our recent adventures (any excuse, eh?).

Note: Save yourself Some Trouble

If you don’t feel like typing out all this content, you can paraphrase, or copy it from the code archive. I’ve deliberately chosen to put a realistic amount of content on the page, so that you can see the effect of several paragraphs on our display.

- Next, add a Contact Us section, again, signified by a level three heading.

- Finally, add some simple contact details as follows:

To find out more, contact Club Secretary Bob Dobalina on 01793 641207 or email [email protected].

So, just to recap, we suggested using different heading levels to signify the importance of the different sections and paragraphs within the document. With that in mind, you should have something like the markup below in the body of your document:

Example 2.9. index.html (excerpt) <h1>BubbleUnder.com</h1> <p>Diving club for the south-west UK - let's make a splash!</p> <h2>Welcome to our super-dooper Scuba site</h2> <p>Glad you could drop in and share some air with us! You've passed your underwater navigation skills and successfully found your way to the start point - or in this case, our home page.</p> <h3>About Us</h3> <p>Bubble Under is a group of diving enthusiasts based in the south-west UK who meet up for diving trips in the summer months when the weather is good and the bacon rolls are flowing. We arrange weekends away as small groups to cut the costs of accommodation and travel and to ensure that everyone gets a trustworthy dive buddy.</p> <p>Although we're based in the south-west, we don't stay on our own turf: past diving weekends away have included trips up to Scapa Flow in Scotland and to Malta's numerous wreck sites.</p> <p>When we're not diving, we often meet up in a local pub to talk about our recent adventures (any excuse, eh?).</p> <h3>Contact Us</h3> <p>To find out more, contact Club Secretary Bob Dobalina on 01793 641207 or email [email protected].</p>

Note: Clickable Email Links

It’s all well and good to put an email address on the page, but it’s hardly perfect. To use this address, a site visitor would need to copy and paste the address into an email message. Surely there’s a simpler way? There certainly is:

<p>To find out more, contact Club Secretary Bob Dobalina on 01793 641207 or <a href="mailto:[email protected]">email [email protected]</a>.</p>

This clickable email link uses the a element, which is used to create links on web pages (this will be explained later in this chapter). The mailto: prefix tells the browser that the link needs to be treated as an email address (that is, the email program should be opened for this link). The content that follows the mailto: section should be a valid email address in the format username@domain.

Add this to the web page now, save it, then refresh the view in your browser. Try clicking on the underlined text: it should open your email program automatically, and display an email form in which the To: address is already completed.

Figure 2.15. Viewing index.html

It’s still not very exciting, is it? Trust me, we’ll get there! The important thing to focus on at this stage is what the content of your site should comprise, and how it might be structured. We haven’t gone into great detail about document structure yet, other than to discuss the use of different levels of headings, but we’ll be looking at this in more detail later in this chapter. In the next chapter, we’ll see how you can begin to style your document — that is, change the font, color, letter spacing and more’but for now, let’s concentrate on the content and structure.

The page so far seems a little boring, doesn’t it? Let’s sharpen it up a little. We can only keep looking at a page of black and white for so long — let’s insert an image into the document. Here’s how the img element is applied within the context of the page’s markup:

Example 2.10. index.html (excerpt) ><h2>Welcome to our super-dooper Scuba site</h2> <p><img src="divers-circle.jpg [22]" width="200" height="162" alt="A circle of divers practice their skills" /></p>

<p>Glad you could drop in and share some air with us! You’ve passed your underwater navigation skills and successfully found your way to the start point – or in this case, our home page.</p>

Whoa, hold up there. Let’s talk about all this img stuff (don’t worry, it’s pretty simple). The img element is used to insert an image into our web page, and the attributes src, alt, width, and height describe the image that we’re inserting. src is just the name of the image file. In this case, it’s divers-circle.jpg, which you can grab from the code archive. alt is some alternative text that can be displayed in place of the image if, for some reason, it can’t be displayed. This is useful for visitors to your site who may be blind (they have web browsers, too!), search engines, and users of slow Internet connections. width and height should be pretty obvious: they give the width and height of the image, measured in pixels. Don’t worry if you don’t know what a pixel is; we’ll look into images in more detail a bit later.

Figure 2.16. Divers pausing in a circle

Go and grab divers-circle.jpg from the code archive, and put it into your web site’s folder. The image is shown in Figure 2.16.

Open index.html in your text editor and add the following markup just after the level two heading (h2):

Example 2.11. index.html (excerpt) <p><img src="divers-circle.jpg" width="200" height="162" alt="A circle of divers practice their skills" /></p>

Save the changes, then view the homepage in your browser. It should look like the display shown in Figure 2.17.

Figure 2.17. Displaying an image on the homepage

Adding Structure

Paragraphs? No problem. Headings? You’ve got them under your belt. In fact, you’re now familiar with the basic structure of a web page. The small selection of tags that we’ve discussed so far are fairly easy to remember, as their purposes are obvious (remember: p = paragraph). But what the heck is a div?

A div is used to divide up a web page and, in doing so, to provide a definite structure that can be used to great effect when combined with CSS.

The strange thing about a div is that, normally, it has no effect on the styling of the text it contains, except for the fact that it adds a break before and after the contained text. Consider the following markup:

<p>This is a paragraph.</p> <p>So is this.</p>

If you were to change those paragraph tags to divs, there would be very little obvious change in the page’s appearance when you viewed it in a browser (as Figure 2.18 shows).

<p>This is a paragraph.</p> <div>This looks like a paragraph, but it's actually a div.</div> <p>This is another paragraph.</p> <div>This is another div.</div>

Figure 2.18. Paragraphs displaying similarly to divs

“But they look exactly the same! What’s the difference between using a div and a p?” you may protest. Well, the purpose of a div is to divide up a web page into distinct sections, adding structural meaning, whereas p should be used to create a paragraph of text.

Note: Use Elements as Intended

Never use an XHTML element for a purpose for which it was not intended. This really is a golden rule!

Rather than leaving the paragraph tags as they are, you might decide to have something like this:

<div>

<p>This is a paragraph inside a div.</p> <p>So is this.</p> </div>

You can have as many paragraphs as you like inside that div element, but note that you cannot place div elements inside paragraphs. Think of a div as a container that’s used to group related items together, and you can’t go wrong.

If we look at our homepage in the browser, it’s possible to identify areas that have certain purposes. These are listed below, and depicted in Figure 2.19. We have:

- a header area that contains:

- the site name

- a tag line

- an area of body content

Figure 2.19 shows how the different segments of content can be carved up into distinct areas based on the purposes of those segments.

Take the homepage we’ve been working on (index.html) and, in your text editor of choice, add <div> and </div> tags around the sections suggested in Figure 2.19. While you’re adding those divs, add an id attribute to each, appropriately allocating the names header, sitebranding, tagline, and bodycontent. Remember that attribute names should be written in lowercase, and their values should be contained within quotation marks.

Figure 2.19. Noting distinct sections in the basic web page

Note: No Sharing ids!

id attributes are used in XHTML to identify elements, so no two elements should share the same id value. You can use these ids later, when you’re dealing with elements via CSS or JavaScript.

Note: h1, header, and head

An id attribute set to header should not be confused with headings on the page (h1, h2, and so on); nor is it the same as the head of your HTML page. The id= attribute could just as easily have been named topstuff or pageheader. It doesn’t matter, so long as the attribute name describes the purpose of that page section to a fellow human being (or to yourself 12 months after you devised it, and have forgotten what you were thinking at the time!).

To get you started, I’ve done a little work on the first part of the page. In the snippet below, that section has been changed to a div with an id attribute:

Example 2.12. index.html (excerpt) <div id="header"> <h1>BubbleUnder.com</h1> <p>Diving club for the south-west UK - let's make a splash!</p> </div> <!-- end of header div -->

Now, try doing the same: apply divs to the parts of the content that we’ve identified as “site branding” and “tag line.”

Nesting Explained

We already know that divs can contain paragraphs, but a div can also contain a number of other divs. This is called nesting. It’s not tricky, it’s just a matter of putting one div inside the other, and making sure you get your closing tags right.

<div id="outer"> <div id="nested1"> <p>A paragraph inside the first nested div.</p> </div> <div id="nested2"> <p>A paragraph inside the second nested div.</p> </div> </div>

As Figure 2.19 shows, some nesting is taking place: the “site branding” and “tag line” divs are nested inside the “header” div.

The Sectioned Page: all Divided Up

All things being well, your XHTML should now look like this:

Example 2.13. index.html <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Bubble Under - The diving club for the south-west UK</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> <div id="header"> <div id="sitebranding"> <h1>BubbleUnder.com</h1> </div> <div id="tagline"> <p>Diving club for the south-west UK - let's make a splash!</p> </div> </div> <!-- end of header div --> <div id="bodycontent"> <h2>Welcome to our super-dooper Scuba site</h2> <p><img src="divers-circle.jpg" width="200" height="162" alt="A circle of divers practice their skills" /></p> <p>Glad you could drop in and share some air with us! You've passed your underwater navigation skills and successfully found your way to the start point - or in this case, our home page.</p> <h3>About Us</h3> <p>Bubble Under is a group of diving enthusiasts based in the south-west UK who meet up for diving trips in the summer months when the weather is good and the bacon rolls are flowing. We arrange weekends away as small groups to cut the costs of accommodation and travel and to ensure that everyone gets a trustworthy dive buddy.</p> <p>Although we're based in the south-west, we don't stay on our own turf: past diving weekends away have included trips up to Scapa Flow in Scotland and to Malta's numerous wreck sites.</p> <p>When we're not diving, we often meet up in a local pub to talk about our recent adventures (any excuse, eh?).</p> <h3>Contact Us</h3> <p>To find out more, contact Club Secretary Bob Dobalina on 01793 641207 or <a href="mailto:[email protected]">email [email protected]</a>.</p> </div> <!-- end of bodycontent div --> </body> </html>

Note: Indenting your Markup

It’s a good idea to “indent” your markup when nesting elements on a web page, as is demonstrated with the items inside the div section above. Indenting your code can help resolve problems later, as you can more clearly see which items sit inside other items. Note that indenting is only really useful for the person — perhaps you! — who’s looking at the source markup. It does not affect how the browser interprets or displays the web page. (The one exception to this is the pre element. pre is short for pre-formatted, and any text marked up with this element appears on the screen exactly as it appears in the source; in other words, carriage returns, spaces, and any tabs that you’ve included will be honored. The pre element is usually used to show code examples.)

Notice that, in the markup above, comments appear after some of the closing div tags. These comments are optional, but again, commenting is a good habit to get into as it helps you fix problems later. Often, it’s not possible to view your opening and closing <div> tags in the same window, as they’re wrapped around large blocks of XHTML. If you have several nested <div> tags, you might see something like this at the end of your markup:

</div> </div> </div>

In such cases, you might find it difficult to work out which div is being closed off at each point. It may not yet be apparent why this is important or useful, but once we start using CSS to style our pages, errors in the XHTML can have an impact. Adding some comments here and there can really help you debug later.

</div> <!-- end of inner div --> </div> <!-- end of nested div --> </div> <!-- end of outer div -->

How does the web page look? Well, we’re not going to include a screen shot this time, because adding those div elements should make no visual difference at all. The changes we just made are structural ones that we’ll build on later.

Note: Show a Little Restraint

Don’t go overboard adding divs. Some people can get carried away as they section off the page, with <div> tags appearing all over the place. Overly enthusiastic use of the div can result in a condition that has become known as “div-itis.” Be careful not to litter your markup with superfluous <div> tags just because you can.

Splitting Up the Page

We’ve been making good progress on our fictitious site … but is a web site really a web site when it contains only one page? Just as the question, “Can you have a sentence with just one word?” can be answered with a one-word sentence (“Yes”), so too can the question about our one-page web site. But it’s not really ideal, is it? You didn’t buy this book to learn how to create one page, did you?

Let’s take a look at how we can split the page we’ve been working on into separate entities, and how these pages relate to each other.

First, let’s just ensure that your page is in good shape before we go forward. The page should reflect the markup shown in the last large block presented in the previous section (after we added the <div> tags). If not, go to the code archive and grab the version that contains the divs). Save it as index.html in your web site’s folder (if you see a prompt that asks whether you want to overwrite the existing file, click Yes).

Got that file ready? Let’s break it into three pages. First, make two copies of the file:

- Click on the index.html icon in Windows Explorer or Finder.

- To copy the file, select Edit > Copy.

- To paste a copy in the same location, select Edit > Paste.

- Repeat the process once more.

You should now have three HTML files in the folder that holds your web site files. The index.html file should stay as it is for the time being, but take a moment to rename the other two (select each file in turn, choosing File > Rename, if you’re using Windows; Mac users, simply select the file by clicking on it, then hit Return to edit the filename).

- Rename one file as contact.html (all lowercase).

- Rename the other one as about.html (all lowercase).

Note: Where’s my File Extension?

If your filename appears as just index in Windows Explorer, your system is currently set up to hide extensions for files that Windows recognizes. To make the extensions visible, follow these simple steps:

- Launch Windows Explorer.#eli#/

- For Windows ME/2000/XP, select Tools > Folder Options… (on Windows 98, this is View > Folder Options…).#eli#/

- Select the View tab.#eli#/

- In the Advanced Settings group, make sure that Hide extensions for known file types does not have a tick next to it.

We have three identical copies of our XHTML page. Now, we need to edit the content of these pages so that each page includes only the content that’s relevant to that page.

To open an existing file in Notepad, select File > Open, and in the window that appears, change Files of type to All Files. Now, when you go to your Web folder, you’ll see that all the files in that folder are available for opening.

Opening a file in TextEdit is a similar process. Select File > Open to open a file, but make sure that Ignore rich text commands is checked.

In your text editor, open each page in turn, and edit them as follows (remembering to save your changes to each before you open the next file):

index.html— Delete the “About Us” and “Contact Us” sections (both the headings and the paragraphs that follow them), ensuring that the rest of the markup remains untouched. Be careful not to delete the<div>and</div>tags that enclose the body content.about.html— Delete the introductory spiel (the level two heading and associated paragraphs, including the image) and remove the “Contact Us” section (including the heading and paragraphs).contact.html— You should be getting the hang of this now (if you’re not sure you’ve got it right, keep reading: we’ll show the altered markup in a moment). This time, we’re removing the introductory spiel and the “About Us” section.

Now, each of the three files contains the content that suits its respective filename, but a further change is required for the two newly created files. Open about.html in your text editor and make the following amendments:

- Change the contents of the title element to read “About BubbleUnder.com: who we are; what this site is for.”

- Change the level three heading

<h3>About Us</h3>to a level two heading. In the process of editing our original homepage, we’ve lost one of our heading levels. Previously, the “About Us” and “Contact Us” headings were marked up as level three headings that sat under the level two “Welcome” heading. It’s not good practice to skip heading levels — anh2followingh1is preferable to anh3following anh1.

Next, open contact.html in your text editor and make the following changes:

- Amend the contents of the title element to read, “Contact Us at Bubble Under.”

- Change the level three heading to a level two heading, as you did for

about.html.

If everything has gone to plan, you should have three files named index.html, about.html, and contact.html.

The markup for each should be as follows:

Example 2.14. index.html <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html > <head> <title>Bubble Under - The diving club for the south-west UK</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> <body> <div id="header"> <div id="sitebranding"> <h1>BubbleUnder.com</h1> </div> <div id="tagline"> <p>Diving club for the south-west UK - let's make a splash!</p> </div> </div> <!-- end of header div --> <div id="bodycontent"> <h2>Welcome to our super-dooper Scuba site</h2> <p><img src="divers-circle.jpg" alt="A circle of divers practice their skills" width="200" height="162" /></p> <p>Glad you could drop in and share some air with us! You've passed your underwater navigation skills and successfully found your way to the start point - or in this case, our home page.</p> </div> <!-- end of bodycontent div --> </body> </html> Example 2.15. about.html <!DOCTYPE html